The Misdiagnosis of Modernity: Henri de Lubac and the Human Hunger for God

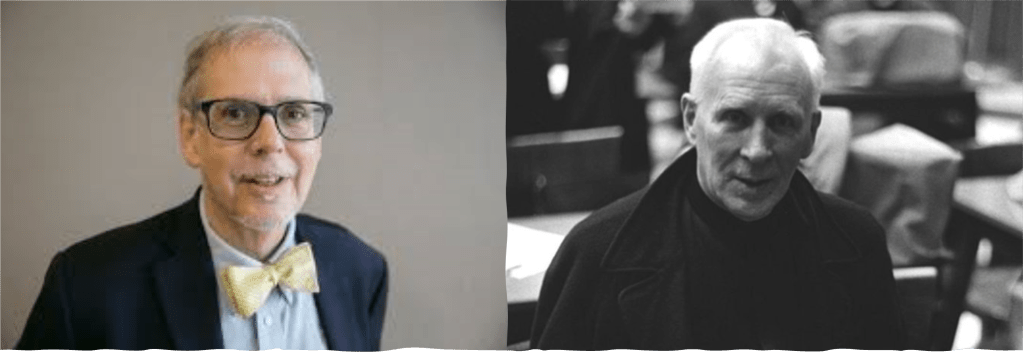

In a recent substack article, Craig A. Carter, a professor of theology at Tyndale University, reviews Steven Long’s Natura Pura: On the Recovery of Nature in the Doctrine of Grace. The book tackles a complex 20th-century debate within Roman Catholic theology concerning the concept of “pure nature” (natura pura). At stake is nothing less than the relationship between human nature and divine grace, and with it, the foundation of natural law and the Church’s engagement with a secular world.

According to Carter’s summary, the traditional Thomistic view—which Long seeks to defend—holds that humans possess two distinct ends: a natural end (happiness attained through reason and virtue) and a supernatural end (the Beatific Vision, granted gratuitously by grace). In this framework, “pure nature” is a coherent philosophical concept, and the maxim “grace does not destroy nature, but perfects it” requires this clear distinction.

Carter explains that Long positions Henri de Lubac as the primary antagonist in this drama. In response to modernism, de Lubac and others of the Nouvelle Théologie sought a “Third Way.” De Lubac argued that the concept of a self-contained “pure nature” was a later misinterpretation of Thomas Aquinas, asserting instead that human nature is inherently and constitutively oriented toward the supernatural. From Long’s perspective, as presented by Carter, this move was a catastrophic error. By rejecting a proportionate natural telos, de Lubac allegedly strips human nature of its intelligibility and ontological density, thereby undermining the rational foundation for natural law and objective morality. The practical consequence, Long argues, is that the Church is left without a philosophical basis for public discourse, relegating morality to the private realm of faith.

I cannot speak to the nuances of Long’s own work, but if Carter’s characterization is accurate, this critique, though powerful, rests on a fundamental misdiagnosis of the problem. It is de Lubac, not his Neo-Thomist critics, who offers the more profound and historically authentic defense of a unified reality against the fissures of modern secularism.

De Lubac’s Deeper Battle: Against the “Two-Story” Universe

It is accurate that de Lubac vigorously attacked the concept of a self-sufficient human nature with a purely natural end (finis naturalis). But his target was not nature itself; it was a specific theological error known as “extrinsicism.” This is the view that grace and nature relate like two separate stories of a building, where the supernatural is an optional penthouse added onto a fully complete and autonomous ground floor.

De Lubac saw this model as theologically disastrous. By rendering the supernatural arbitrary, it implicitly suggests that human beings can be understood as a closed system without reference to God. He believed this very abstraction—this philosophical fiction of a purely self-contained nature—paved the way for modern secularism. The secular world simply accepted the ground floor that theologians had already declared independent and proceeded to live in it as if God did not exist.

Recovering a Participatory Ontology

Contrary to the charge of undermining nature, de Lubac sought to restore its deepest intelligibility by rediscovering its inherent relationality. He argued that the very constitution of the human person includes a natural desire for the supernatural (desiderium naturale visio beatificae). This is not a mere conscious yearning but an ontological orientation woven into our spiritual nature.

Think of fish. A fish can be described anatomically, but its nature only makes complete sense in relation to water. For de Lubac, human nature only finds its full intelligibility in relation to God. Therefore, grace is not an extrinsic addition but the fulfillment of an intrinsic, God-given orientation. It perfects nature by answering the deepest call of that nature itself.

This recovery of a participatory worldview connects de Lubac directly to the ancient philosophical traditions that shaped the Church Fathers.

- Plato’s Inheritance: The Platonic tradition teaches that the physical world participates in a higher, more real world of Forms. Nothing in the sensible world is intelligible or good on its own; it derives its being and value from these transcendent realities. De Lubac’s theology is profoundly participatory. To define nature without its supernatural referent is, in a Platonic sense, to study the shadow while ignoring the reality casting it.

- Aristotle’s Teleology, Perfected: Aristotle’s core principle is that everything has a telos—a purpose built into its very being. Aquinas baptized this idea. The critical question is: does the natural telos of a human being provide its final and ultimate end? The Neo-Thomist says yes, positing a closed, natural end. De Lubac, arguing for what he believes is Aquinas’s true view, says no. The deepest desires of the intellect for truth and the will for goodness are inherently open-ended and limitless; they cannot be satisfied by any created end. The natural telos of the human spirit is, therefore, a receptive orientation toward the Infinite.

A Clash of Diagnoses

This leads to the heart of the conflict: a starkly different analysis of the “disease” of secularism.

- The Long/Carter Diagnosis: The modern problem is the loss of a rational foundation for nature. The remedy is to re-assert a robust, autonomous (though God-created) natural order knowable by reason alone.

- The De Lubac Diagnosis: The modern problem was caused by the creation of a self-enclosed concept of nature. The remedy is to heal the fracture by recovering the truth that nature is inherently ordered toward the supernatural.

From de Lubac’s perspective, the Long/Carter project tries to cure the disease by administering more of the poison. Re-asserting “pure nature” merely reinforces the very concept that allowed the secular world to declare its independence.

This is ultimately a conflict of hermeneutics, a disagreement over how to read the tradition. Does one prioritize systematic, logical distinctions (Long’s approach), or unifying, participatory themes (de Lubac’s approach)?

The remarkable vindication of de Lubac’s project is that his core insights, though once controversial, were largely incorporated into the Second Vatican Council and profoundly influenced popes like Benedict XVI and John Paul II. They recognized in his work not a capitulation to modernity, but a powerful tool for evangelizing it—one that speaks to the “desire for God” written on every human heart.

In the end, the “pure nature” framework, in its well-intentioned effort to protect grace, inadvertently creates a philosophical abstraction that severs nature from its source and end. De Lubac, by contrast, calls us back to a more ancient and coherent vision: that in the real, concrete order of God’s creation, our nature is not a neutral container that then receives a call; it is a nature that is constituted by that call. To separate them is not to protect nature, but to do violence to the integrity of the creature God actually made.