De-centring the Scientific Revolution, Paley’s Natural Theology, Mobilizing a Prophetic Newton, and Maxwell’s Design Argument

Posted on January 7, 2014 Leave a Comment

I still have several articles open on my pdf reader that are worth mentioning before I officially end my reading of The British Journal for the History of Science, and before tackling other articles from other journals and books.

In discussions over the historiography of the “Scientific Revolution,” almost all the authors I have recently read have mentioned Andrew Cunningham and Perry Williams’ “De-centring the ‘big picture’: The Origins of Modern Science and the Modern Origins of Science” (1993). They argue that a big picture of the history of science cannot be avoided, and that “big pictures are both necessary and desirable.” Indeed, the “big picture” is crucial, if not necessary, for giving any localized, “small picture” meaning. But in saying this, Cunningham and Williams also want to expose and reconstruct the aims of the founders of the “old big picture” of the history of science (Herbert Butterfield and his followers), which maintained that “science…[is as] old as humanity itself.” This was a single, grand, and sweeping history of science.

Without usurping this “old big picture,” Cunningham and Williams want to promote a different account, one that emphasizes the idea that our world is fragmented into a plurality of local, autonomous discourses, and based on principles of postmodernism and poststructualism. They then rehearse the problems which have arisen with the concept of the “Scientific Revolution” since Butterfield. Modern notions of the scientific revolution derive from conceptions of science in the early and mid-twentieth century, including positivist definition of “science as a particular method of enquiry” that produces “knowledge in the form of general causal laws”; as essentially moral, “as the embodiment of basic values of freedom and rationality, truth and goodness”; and as a “universal human enterprise,” which emanates from some innate, human curiosity. In the 1940s, historians of science incorporated these characterizations of science as they developed the concept of the scientific revolution. In short, they projected their own contemporary definitions of science onto past.

According to Cunningham and Williams, such a view of the “Scientific Revolution” is no longer tenable. The “new big picture,” they argue, should view science as a contingent enterprise reflecting the aims and morals of a particular social group in a particular historical time; one among a plurality of ways of knowing the world, it must be seen as limited, bounded in time and space and culture. In their estimation, the origins of science “can be located in Western Europe in the period sometimes known as the Age of Revolutions—approximately 1760-1848.” “Every feature which is regarded as essential and definitional of the enterprise of science,” they write, is identifiable during the Age of Revolutions: “its name, its aim, its values, and its history.” On this view, “the history of science becomes a relatively short and local matter.” This realization, they maintain, is “de-centring,” in the sense that we realize “that external objects have permanence, that other people can have different knowledge, interests, feelings, and so on.” It is a shedding of egotism. “To see science as a contingent and recently-invented activity is to make such a de-centring, and to acknowledge that things about our primary way-of-knowing which we once thought were universal are actually specific to our modern capitalistic, industrial world.”

For those interested in the history of the publication, teaching, reception, and use of natural theology in the nineteenth century, Aileen Fyfe’s essay “The Reception of William Paley’s Natural Theology in the University of Cambridge” (1997) is essential reading. Studying the examination papers of the University of Cambridge, contemporary memoirs, autobiographies and correspondences, reveals, Fyfe argues, that Paley’s Natural Theology (1802) was not a set text at the university in the early nineteenth century. “Theology proves to have been a relatively minor part of the formal curriculum, and natural theology played only a small role within that.”

Writing in his dedication page in Natural Theology, William Paley (1743-1805) maintained that three of his books contained “the evidences of Natural Religion, the evidences of Revealed Religion, and an account of the duties that result from both.” The most recent was his Natural Theology (1802), preceded by his A View of the Evidences of Christianity (1794) and the Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy (1785). By all measures, Natural Theology was a great success, going to “through fifteen editions in as many years, and while the print runs are not known, this suggests sales of around 15,000 copies.” Reviews from Edinburgh Review, Monthly Review, Monthly Magazine, and Churchman’s Magazine found it most agreeable, and some even “mentioned its educational potential.” Some reviewers from the Evangelical Magazine, however, worried that Natural Theology would lead readers to “dangerously conclude that no other religion [that is Scripture] is necessary to their eternal salvation.” English politician, philanthropist, and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade, William Wilberforce (1759-1833) wrote in the Christian Observer that Paley’s assertions were “both untenable and unsafe…We are the more suspicious of the sentiment…because we recollect that it was made the ground of the theological system of [the noted deist and radical] Thomas Paine.” As Fyfe write, some “Evangelicals associated Paley’s work with deism…[and] with [the] radicalism after the French Revolution.”

Despite these criticism, Paley’s Natural Theology was immensely popular. Moreover, when Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859) emerged, “natural theology did not suddenly end in 1859,” a point Jon H. Roberts cogently confirms in his entry in Ron Numbers’ (ed.) Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion (2009). But as far as being a set text at Cambridge, Paley’s Natural Theology was not used. Natural theological questions “rarely occurred in university or college examination,” and thus natural theology never quite achieved “equality with revealed theology.” As Fyfe concludes, “natural theology did not have very much formal recognition in the mathematical University of Cambridge at a time when Evangelicalism was spreading and deism was threatening. It could have been recognized only as a defense for theology or as an implicit background assumption for the natural sciences.”

Those curious about “geographies of reading”—I stand convicted—may turn to David N. Livingstone’s corpus, particularly (but not most importantly) his “Science, Religion, and the Geography of Reading: Sir William Whitla and the Editorial Staging of Isaac Newton’s Writing on Biblical Prophecy” (2003). “Writings of eminent scientists,” Livingstone claims, “can be mobilized in the cause of local cultural wars.” And indeed they have.

Isaac Newton’s insistence that nature follows mathematical laws, for example, was marshalled by seventeenth-century churchmen both to mount assaults on atheism and to curb radical inclinations towards religious enthusiasm. At the same time, the Newtonian system was also enlisted in contemporary debates about the role of the monarchy, the nature of the state and the constitution of the social order. In more recent times, American creationists have called upon the doctrines of earlier scientists as self-justification for their own credo, while those inclined towards theistic evolution have likewise sought reinforcement from earlier advocates of a Christianized Darwinism.

These are tactics in the “attempt to create a suite of canonical scientific texts to serve the needs of some particular sensibilities.” In this way Livingstone wants to draw our attention “to the consumption sector of the scientific knowledge circuit, to the different ways texts were received in different localities and to the spaces in which theories were encountered and textual meaning made.” From Robert Chambers, Alexander von Humboldt, to Charles Darwin’s corpus, “the meaning of texts…shifts from place to place, and at a variety of different scales.”

Six years after his death, Isaac Newton’s commentary on the biblical books of Daniel and Revelation was published in 1733 as Observations upon Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John. In Two Parts. Nearly two hundred years after this first appearance, William Whitla, professor of Materia Medica at the Queen’s University of Belfast, in 1922 made Newton’s text available again to the reading public, under the title Sir Isaac Newton’s Daniel and the Apocalypse with an Introductory Study of the Nature and the Cause of Unbelief, of Miracles and Prophecy.

Whitla was fascinated with the prophetic writings of the Jewish prophets. He was also good friends with William Bramwell Booth, General of the Salvation Army, and dedicated the new book to him. Whitla wanted to use the book against those who were undermining the authority of the sacred text. Newton, who “in strong and childlike faith lent his mighty intellect to the study of this fascinating record.” As Livingstone puts it, “the aim was to muster biblical prophecy Newtonian-style in the conduct of current culture wars.” With the outbreak of the First World War, W.B. Yeats fearing the “reversal of Christian values,” and the 1920s “heresy trail of J. Ernest Davy in Northern Ireland, Whitla saw all these “ominous signs” as “an unmistakable mark of the ‘latter days’ which are to terminate the present dispensation.” Moreover, the “moral leprosy” of biblical critics was spreading “into the heart of the Church itself.” Whitla would use Newton to counter this European crisis.

Ironically Whitla did not “broadcast the fact that Newton had come to doubt the accuracy of the textus receptus of the New Testament”; and neither did he mention that Newton had rejected the doctrine of the Trinity. Whitla also used Newton for anti-Catholic propaganda, re-staging Newton’s own anti-Catholicism, equating the Papacy with the “autocracy of the most satanic character.” Whitla thus valorized Newton’s text as a Protestant polemic. “All of this serves,” Livingstone concludes, “to underscore the salience of textual performance, spaces of reading and sites of reception in elucidating the dynamic geographies of scientific knowledge and religious belief.”

And finally, an intimate and complex relationship between religion and scientific practice is demonstrated in Matthew Stanley’s recent “By Design: James Clerk Maxwell and the Evangelical Unification of Science” (2012). Stanley argues that Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879), known for his formulation of a set of equations that united electricity, magnetism, and optics into a consistent theory, “saw a deep theological significance in the unification of physical laws.” This search for unification was connected to Maxwell’s “particular evangelical religious views.”

Stanley also wants to compare and contrast Maxwell’s own design argument with Paley and those of the modern Intelligent Design (ID) theory. According to Stanley, “both Paley and [Michael] Behe [known for his molecular arguments of “irreducible complexity”] argue that a certain level of complexity could never be explained by naturalistic science, and thus the search for such explanations must stop.” Although Maxwell embraced claims of natural theology, “his evangelical religiosity gave him a rather different perspective.”

Maxwell believed that nature was like a book, with each element a manifestation of a deeper unifying principle. The connections between laws were a sign from above: “…the laws of nature are not mere arbitrary and unconnected decisions of Supreme Power, but that they form essential parts of one universal system, in which infinite Power serves only to reveal unsearchable Wisdom and eternal Truth.” The interrelationship of natural laws “was a way that God communicated His existence, and it was the unity of laws that revealed this communication.” Indeed, the “unity of nature was…guaranteed by theology.” Thus whereas “Paley emphasized complexity as the indicator of God’s hand, Maxwell emphasized unity.”

Stanley notes that Paley, Behe, and Maxwell would all agree that Darwinian evolution was not a reliable scientific theory. For his part, however, Maxwell argued that “Darwinian evolution relied on pre-existing variation, and thus perfectly uniform molecules could never have evolved.” His rejection of Darwinian evolution thus relied on his understanding of unity in nature, not complexity.

As a conservative evangelical Christian, Maxwell had specific notions about the nature of God. Victorian evangelicalism, Stanley tells us, was a “‘religion of the heart,’ with an emphasis on conversion, sin and grace, and moving away from the rationalizism of the Enlightenment in an attempt to resurrect the lost, primitive Church uncontaminated by human failings.” In the summer of 1853, Maxwell gained a newfound evangelical outlook. Maxwell wrote:

I maintain that all the evil influences that I can trace have been internal and not external, you know what I mean—that I have the capacity of being more wicked than any example that man could set me, and that if I escape, it is only by God’s grace helping me to get rid of myself, partially in science, more completely in society,—but not perfectly except by committing myself to God as the instrument of His will, not doubtfully, but in the certain hope that that Will will be plain enough at the proper time.

Divine grace, submission to God, Christology, and Scripture were constantly upon his mind, as his letters to friends and relatives show. From this evangelical perspective, Maxwell saw humanity as “fallen, sinful and fallible.” But “God gave humans the ability to see his actions,” if they would only “embrace Him fully.” Revelation was ultimately mysterious, but so was nature, according to Maxwell: “I have endeavoured to show that it is the peculiar function of physical science to lead us to the confines of the incomprehensible, and to bid us behold and receive it in faith, till such time as the mystery shall open.” In his inaugural lecture at Aberdeen in 1856, Maxwell clearly shows how his theology of nature was manifested in his physical science:

Is it not wonderful that man’s reason should be made a judge over God’s works, and should measure, and weigh, and calculate, and say at last ‘I understand I have discovered—It is right and true’…we see before us distinct physical truths to be discovered, and we are confident that these mysteries are an inheritance of knowledge, not revealed at once, lest we should become proud in knowledge, and despise patient inquiry, but so arranged that, as each new truth is unravelled it becomes a clear, well-established addition to science, quite free from the mystery which must still remain, to show that every atom of creation is unfathomable in its perfection. While we look down with awe into these unsearchable depths and treasure up with care what with our little line and plummet we can reach, we ought to admire the wisdom of Him who has arranged these mysteries that we find first that which we can understand at first and the rest in order so that it is possible for us to have an ever increasing stock of known truth concerning things whose nature is absolutely incomprehensible.

Stanley writes, “Maxwell’s God was a teacher who wanted his students to learn all the details of the world, which He organized in such a way as to help them in their studies.”

Preaching at the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the Secularism of George Jacob Holyoake

Posted on January 5, 2014 1 Comment

Wrapping up a series of essays I have been reading from The British Journal for the History of Science, I now come to two interrelated and complimentary essays by Ciaran Toal, “Preaching at the British Association for the Advancement of Science: Sermons, Secularization and the Rhetoric of Conflict in the 1870s” (2012), and Michael Rectenwald, “Secularism and the Cultures of Nineteenth-century Scientific Naturalism” (2013).

Toal argues that there was a “vast homiletic literature preached during the British Association meetings throughout the nineteenth century, ” despite Reverend Vernon Harcourt’s—one of the founders of the BAAS—dedication to neutrality and admonition against any discussion of religion and politics. As Toal writes in another context (see his “Science, Religion, and the Geography of Speech at the British Association: William Henry Dallinger (1839-1909) Under the Microscope” [2013]), “concerned that the BAAS would become embroiled in theological disputes, and distracted from its mission of bringing science to the provinces, [Harcourt], along with the rest of the leadership, founded the Association as a ‘neutral’ body.”

However, the Sunday of the BAAS meeting, and the sermons preached on that day, constitutes an indelible part of its history. Toal’s essay “focuses on the range of sermons preached in connection with the British Association meetings in the 1870s,” and particular “attention is given to the differing views on the relationship between science and religion in the homiletic record, and the rhetoric of ‘science-religion conflict’ following John Tyndall’s 1874 ‘Belfast Address.'”

In an age often described as the “golden age of preaching,” sermons played an important role in the social and religious life of the Victorian. “Thomas Henry Huxley,” for example, “recognized the cultural power of the sermon, naming his own collection of essays, addresses and reviews ‘Lay Sermons.'”

The religious geography of nineteenth-century Britain often dictated what was preached during the British Association meeting. Although multifarious in style, content, proclamation, and instruction, the most important function of any sermon was the imparting of religious truth. In other words, sermons were didactic, especially those preached at the BAAS.

Sermons preached at the BAAS were responsive to the expectations and sensibilities of its audience. They were not your normal Sunday service, as Toal points out, for the preachers who preached on a Sunday of the BAAS “were aware that their discourses would be widely published and digested.”

Thus lines were often blurred between official BAAS business and associated religious activity. Broadly, sermons were either preached in the week preceding, the week during, or the week immediately following the visit of the BAAS to a host town or city, and directly addressing the prominent scientific issues under discussion.

Turning to the content of sermons and the varying views on the relationship between science and religion in them, Toal reiterates John Hedley Brooke’s warning that discussing science and religion in essentialist terms often obfuscate understanding by importing anachronistic boundaries. But he also argues that “many of the preachers did discuss science and religion in discrete terms, before commenting on how they were or were not related.” For example, a 1870 sermon by Rev. Abraham Hume preached the Connexion between Science and Religion: A Sermon Preached at Christ Church Kensington, Liverpool, 18th September…during the Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Hume quoted from Psalm 100.24, 25 “O Lord, how manifold are thy works! In wisdom hast thou made them all; the earth is full of thy riches. So is the great and wide sea, wherein are things creeping innumerable.” He used the passage to argue that God’s works in nature and God’s word in Scripture both reveal him and our allies. Even more explicit, Anglican Charles Coombe, in 1879, preached a sermon entitled ‘Sirs, Ye are Brethren;’ or Science and Religion at One: Sermon Preached in St. Paul’s Church, Sheffield, on the Occasion of the Meeting of the British Association, August 24th, where he argued against antagonism between science religion, and that both should stop “maligning, fighting and devouring” each other.

In general, according to Toal, three positions in the relationship between science and religion dominate the sermons preached throughout the 1870s. First, the relationship between science religion was underpinned by the idea that they were essentially separate entities. This is usually the position taken by liberal Anglicans and the Unitarians, who were more open to “speculative science.” Other Unitarians, such as itinerant preacher Charles Wicksteed, wanted to separate science and religion into spheres of physical and spiritual knowledge, “as they were different modes of God’s voices, and [thus] should not be judged against each other.” But a number of preachers also maintained that science and religion were integrated as inextricably linked forms of knowledge. Those who took this position often preached that science and its conclusions had to be limited by religion: “relation is crucial, as it could provide a fuller interpretation of nature and, more importantly, offer salvation for nature could not.” Those who took up this position often expressed the views that physical and experimental science, and especially the theories of Darwin, sought to destroy religion. They were also the fiercest critics of Tyndall.

With these “positional readings” in mind, Toal turns specifically to the conflict rhetoric before and after Tyndall’s Belfast Address in 1874. According to Toal, before Tyndall’s attack, preachers explained any science-religion antagonism as a result of either human error, inept theology, over eagerness, a lack of full knowledge of both science and religion, or inattention to the “varieties of God’s voices.” After the Belfast Address, the tone of sermons changes, and, importantly, preachers began leveling “accusation for promoting science-religion conflict at a distinct group, or groups, particularly the scientific naturalists.”

But these accusations had little effect on the reputation of the BAAS. According to Toal, throughout the sermon record in the 1870s, in the context of hostility to religion, the BAAS was without exception received favorably; that is, little criticism is ever directed at the BAAS as a body. This demonstrates, according to Toal, that preachers deliberately differentiated between the BAAS and the antagonistic statements of some of its members. This shows that the responsibility for propagating antagonistic science-religion is rhetoric was identified with a particular group, often labeled as “dogmatic scientists,” “materialists,” “atheists,” or “unbelievers,”and not with the BAAS as a whole. In short, the BAAS was seen, broadly, as an institution favorable to religion and religious groups.

Toal concludes his essay with a note on how “the explanatory power of a ‘secularization thesis’ is diminished in the context of the vast number of Sunday sermons preached at the [BAAS].” “Victorian culture,” he adds, “was arguably no less religious in 1870s than it had been before…[and], similarly, many Victorian scientists were no less religious.”

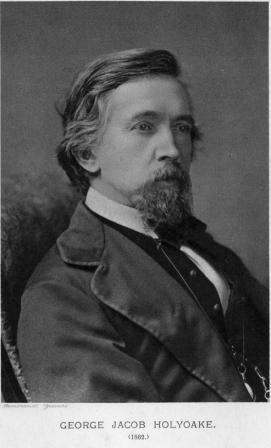

Rectenwald’s essay nicely compliments Toal’s, in which he argues that in the mid-1840s, a philosophical, social and political movement named Secularism evolved from the radical tradition of Thomas Paine, Richard Carlile, Robert Owen and the radical periodical press. George Jacob Holyoake (1817–1906) founded and named Secularism at mid-century, and it was this Secularism that acted as a “significant source for the emerging new creed of scientific naturalism in the mid-nineteenth century.”

Rectenwald’s essay nicely compliments Toal’s, in which he argues that in the mid-1840s, a philosophical, social and political movement named Secularism evolved from the radical tradition of Thomas Paine, Richard Carlile, Robert Owen and the radical periodical press. George Jacob Holyoake (1817–1906) founded and named Secularism at mid-century, and it was this Secularism that acted as a “significant source for the emerging new creed of scientific naturalism in the mid-nineteenth century.”

Rectenwald writes, “Secularism drew from the social base of artisan intellectuals who came of age in the era of self-improvement; the diffusion of knowledge; and agitation for social, political and economic reform—but it also enrolled the support of middle-class radicals.” Holyoake developed secularism as a creed with a naturalistic epistemology, morality, and politics; its principle as an ontological demarcation stratagem, “dividing the metaphysical, spiritual or eternal from ‘this life’—the material, the worldly or the temporal.” But Holyoake’s secularism did not require atheism as a prerequisite; “secularism represented ‘unknowingness without denial.” As Rectenwald puts it, “one’s beliefs in the supernatural were a matter of speculation or opinion to which one was entitled, unless such beliefs precluded positive knowledge or action.” And unlike Charles Bradlaugh’s (1833-1891) politically active atheism, Holyoake’s secularism was not aimed at “abolishing religious ideology from law, education and government.” In short, “secularism represented the necessary conciliation with respectable middle-class unbelief and liberal theology that would allow for an association with the scientific naturalism of Huxley, Tyndall and Spencer,” and as such it was “constitutive of the cultural and intellectual environment necessary for the promotion and relative success of scientific naturalism beginning in the 1850s.”

There was indeed a “circuit of exchanges” between Holyoake and the scientific naturalists, suggesting that secularism was important to scientific naturalism from the outset. Rectenwald gives us fascinating overview of secularism in the periodicals, pamphlets, and other publications with which Holyoake was associated with in the mid-century. Freethought periodicals such as Oracle of Reason—with its epigraph on the front of every issue, “Faith’s empire is the World, its monarch God, its minister the priests, its slaves the people”—Movement and Anti-persecution Gazette, The Investigator, and the Free Thinkers’ Information for the People were founded in the 1840s and “began as working-class productions aimed at working-class readers.” The Oracle of Reason proudly boasted that it was “the only exclusively atheistical print that has appeared in any age or country.”

When Holyoake took over many of these radical publications, he opened the pages to “respectable” radicals, such as Herbert Spencer and Auguste Comte, forming an alliance between radical artisans and middle-class unbelievers. As many historians have shown, Lamarck’s theory of evolution was taken up by various radical political thinkers, which seemed to provide scientific underpinning for their reformist political views. Rectenwald recounts how “evolutionary ideas were marshaled to counter a static, hierarchical, theocratic social order with a vision of a transformative, ‘uprising’ nature” in the pages of the radical press, particularly under Holyoake’s editorship.

In late 1849 Holyoake joined the radical journalist Thornton Hunt’s (1810-1873) group, Confidential Combination, with the vision of enlisting “wary middle-class freethinkers into an anonymous groups where they might voice advanced opinion on ‘politics, sociology, or religion’ without fear of reprisal.” According to Rectenwald, this group “no doubt included…Herbert Spencer, W. Savage Landor, W.J. Linton, W.E. Forster, T. Ballatine and George Hooper,” all of whom contributed to the radical press. In their meetings, Holyoake regularly met with Spencer, becoming “lifelong friends, with regular correspondence continuing to 1894.”

This same circle of London writers often met at the publishing of John Chapman, the publisher of the Westminster Review, “the organ of philosophical radicalism.” The gatherings consisted of contributors George Eliot (the pen name of Mary Ann Evans), Spencer, Harriet Martineau, Charles Bray, George Combe and Thomas Henry Huxley. It was through Martineau and Eliot that Holyoake “came to know Comte’s ideas” in the Positive Philosophy. It was also here where Holyoake began a friendship with Huxley.

In the early 1860s, Holyoake “regularly corresponded with Spencer, Huxley and Tyndall.” According to Rectenwald, “the letters covered numerous issues, including polemics against religious interlocutors, the mutual promotion of literature, the naturalists’ financial and written support for Secularism and Secularists and health, amongst other topics.” And when Huxley sought to dissociate himself from materialism and coarse atheism, his association with Holyoake’s secularism offered a “respectable” alternative. Tyndall also once extolled Holyoake as an exemplar of secular morality. This correspondence was not merely professional, but, as Rectenwald points out, quite personal, as when each man supported, morally and financially, the other during certain illnesses.

Rectenwald demonstrates, by careful readings of a vast array of radical publications and personal correspondence, “the importance of freethought radicalism to the emergence of the powerful discourse of scientific naturalism” in the second half of the nineteenth century. Holyoake in particular “modified freethought by pruning its atheistic rhetoric, allowing freethinkers to discount the supernatural and to disavow the clergy in matter relating to knowledge and morals, without the expected bombast and negation.” Popular among an audience of sophisticated working-class and lower-middle-class readers, Holyoake’s secularism “did much to advance the world view developed and promulgated by Huxley and Tyndall.”

John William Draper’s “Metaphysical Pathos” in his A History of the Intellectual Development of Europe

Posted on January 3, 2014 1 Comment

I have been reading Donald Fleming’s John William Draper and the Religion of Science (1972) today and came to a remarkable discovery. In Chapter VIII, Fleming makes some brief comments on Draper’s A History of the Intellectual Development of Europe (1862). In Draper’s preface to this work, he says:

In the Preface to the second edition of my Physiology, published in 1858, it was mentioned that this work was at that time written. The changes that have been since made in it have been chiefly with a view of condensing it. The discussion of several scientific questions, such as that of the origin of species, which have recently attracted public attention so strongly, has, however, remained untouched, the principles offered being the same as presented in the former work in 1856.

According to Fleming, “this is clearly designed to meet the challenge that [Draper] cribbed from Darwin….[and] may, or may not, be intended to show also that [he] had finished his book before the appearance of the first volume of H.T. Buckle’s History of Civilization in 1857,” which Joseph Hooker, after the Oxford debate of 1860, had accused him of copying without its seasoning.

Also fascinating, Fleming claims that “Draper tried to sketch the pattern of his history after the manner of Aguste Comte,” where nations have passed from theology through metaphysics to positive, scientific thought. But Draper provides a nuance. He “explored the relation of the environment of peoples to their history, and made of enveloping Nature the compulsive force behind all of history.” “Naturalistic evolution is a substitute for the anthropomorphic God who laid down orderly decrees; and the law of [Comte’s] three stages is a secular version of these decrees.”

Furthermore, Fleming sees three distinct traditions “mingling and dissevering” in Draper’s intellectual, European history. Here I note the first, which is a Christian theology, in which Draper substitutes the God the father and God the judge for a God the engineer. “Among the Christian dogmas transmitted by Draper full-strength,” Fleming writes, “was the comprehension of the world at a gulp. He crammed his zest for scientific innovation well within the bounds of basic security about the nature of things. From change and confusion he pointed to stability and order.” Like Darwin, Draper rejected special creation because it robbed God of his integrity:

…it is a more noble view of the government of this world to impute its order to a penetrating primitive wisdom, which could foresee consequences throughout a future eternity, and provide for them in the original plan at the outset, than to invoke the perpetual intervention of an ever-acting spiritual agency for the purpose of warding off misfortunes that might happen, and setting things to rights.

To operate by expedients is for the creature, to operate by law for the Creator; and so far from the doctrine that creations and extinctions are carried on by a foreseen and predestined ordinance—a system which works of itself without need of any intermeddling—being an unworthy, an ignoble conception, it is completely in unison with the resistless movements of the mechanism of the universe, with whatever is orderly, symmetrical, and beautiful upon earth, and with all the dread magnificence of the heavens.

Indeed, there is a “metaphysical pathos” in Draper’s history. “God has been emptied out upon ‘nature,'” and in ways similar to John Tyndall, Draper’s Intellectual Development displays a “strong, if not rigorous, strain of pantheism.”

This attitude is part and parcel of a tradition within nineteenth-century Protestant theology, which “drew back from describing God’s form.” While Draper has nothing but contempt for “antropoid conceptions” of God, he also sees science as providing mankind with much needed humility.

Is the earth the greatest and most noble body in the universe, round which, as an immovable centre, the sun, and the various planets, and stars revolve, ministering by their light and other qualities to the wants and pleasures of man, or is it an insignificant orb—a mere point—submissively revolving, among a crowd of compeers and superiors, around a central sun? The former of these views was authoritatively asserted by the Church; the latter, timidly suggested by a few thoughtful and religious men at first, in the end gathered strength and carried the day.

Behind this physical question—a mere scientific problem—lay something of the utmost importance-the position of man in the universe.

The result of the discoveries of Copernicus and Galileo was thus to bring the earth to her real position of subordination and to give sublimer views of the universe.

If we ignore the obvious mythological character in this account, it should not deter us from seeing that, for Draper, it was the glory of science that gave man a properly low estimate of his own importance. As Fleming observes, “it is hard to escape the conclusion that this view of science springs from the flagellation of man and the denigration of earthly existence in the Christian tradition.”

Darwin’s Rhetoric of Positive Theology in the Origin of Species

Posted on January 2, 2014 1 Comment

In his Of Apes and Ancestors: Evolution, Christianity, and the Oxford Debate (2009), Ian Hesketh stresses that the Origin, “far from being the secular text it is often presented as, establishes the theory of evolution from within the Christian framework.” Indeed, “Darwin was very careful to at least appear to be writing from within the tradition of natural theology.” Such claims may cause consternation for some, as in the case, for example, of one particular reviewer of Hesketh’s book on Amazon. This particular reviewer cites some prominent scholars for support: Harvard historian of science Janet Browne, evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, and even the legendary iconoclast John Hedley Brooke as allegedly “discrediting” Hesketh’s claim. Had the reviewer more carefully examined the dust jacket, however, he would have noticed that Brooke highly recommends the book.

In his Of Apes and Ancestors: Evolution, Christianity, and the Oxford Debate (2009), Ian Hesketh stresses that the Origin, “far from being the secular text it is often presented as, establishes the theory of evolution from within the Christian framework.” Indeed, “Darwin was very careful to at least appear to be writing from within the tradition of natural theology.” Such claims may cause consternation for some, as in the case, for example, of one particular reviewer of Hesketh’s book on Amazon. This particular reviewer cites some prominent scholars for support: Harvard historian of science Janet Browne, evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, and even the legendary iconoclast John Hedley Brooke as allegedly “discrediting” Hesketh’s claim. Had the reviewer more carefully examined the dust jacket, however, he would have noticed that Brooke highly recommends the book.

More importantly, this particular reviewer actually misreads Hesketh’s commentary on Darwin’s Origin. Hesketh is not maintaining that the Origin was a particularly “Christian work”; rather, according to Hesketh, Darwin was keen on employing a particularly religious rhetoric throughout the book (and even more particularly, a Christian positive theological framework). This is especially true of the earliest editions. This is a peculiar misunderstanding—or omission—from this Amazon reviewer, considering that he maintains to have read facsimiles of the first edition of the Origin. In his zeal, this Amazon reviewer has taken passages from Browne, Mayr, and Brooke, wrested them out of their contexts, and applied them against claims that bear no relevance. That is, he not only misconstrues Hesketh’s claims, he also misconstrues claims by Browne, Mayr, Brooke, and, more egregiously, the text of Darwin’s Origin.

Besides a more careful reading of Origin, a helpful correction of this sort of thinking, and a helpful clarification of Hesketh’s claims in Of Apes and Ancestors, comes from Stephen Dilley’s “Charles Darwin’s use of theology in the Origin of Species,” found in the 2012 issue of The British Journal for the History of Science, and John Angus Campbell’s “Charles Darwin: Rhetorician of Science” in John S. Nelson, Allan Megill, and Donald N. McCloskey (eds.), The Rhetoric of the Human Sciences: Language and Argument in Scholarship and Public Affairs (1987).

Dilley argues that Darwin utilized positiva theology in order to justify (and inform) descent with modification and to attack special creation. By incorporating “God-talk” into the Origin, Darwin borrowed “from natural theology similar research problems, presuppositions, patterns of argumentation, metaphors, concepts and content.”

Darwin chose a particular passage from William Whewell’s Bridgewater Treatise to act as an epigraph for the Origin:

But with regard to the material world, we can at least go so far as this—we can perceive that events are brought about not by insulated interpositions of Divine power, exerted in each particular case, by the establishment of general laws.

Near the end of the Origin, Darwin also writes:

Authors of the highest eminence seem to be fully satisfied with the view that each species has been independently created. To my mind it accords better with what we know of the laws impressed on matter by the Creator, that the production and extinction of the past and present inhabitants of the world should have been due to secondary causes, like those determining the birth and death of the individual.

In Darwin’s view, natural laws are unbroken. He claimed that “Everything in nature is the result of fixed laws.” As Dilley points out, “Darwin’s early notebooks…[endorsed] divine creation by law as ‘far grander’ than specific instances of creation by miracle, which were ‘beneath the dignity of him, who is supposed to have said let there be light & there was light.'” In short, Darwin rejected miracles and instead favored unbroken natural law, a belief found also in a number of Darwin’s intellectual mentors, including Whewell, John Herschel, Charles Babbage, and Francis Bacon. These authors all expressed the idea of “God inscribing matter with enduring, lawful qualities.” This allusion to a Master Architect rather than a Miracle Worker not only played a role in Darwin’s argument for evolution, but, as Dilley argues, “it may also have influenced the content of his theory itself.” A deistic theology commends a process of random variation, of purely secondary causes, which is the heart of Darwin’s theory.

The problem of pain also informed Darwin’s theory. “In the Origin,” writes Dilley, “Darwin argues that suffering itself was evidence for his theory: since natural suffering is more compatible with evolutionary theory than with special creation, it counted as evidence in favour of evolution.” In several places in the Origin and in his later autobiography, Darwin remarked that “‘the existence of suffering’ counts ‘against the existence of an intelligent first cause’ but ‘agrees well with the view that all organic beings have been developed through variation and natural selection.'” A benevolent, all-powerful, all-knowing God of special creation could not permit, according to Darwin, the pattern of death and cruelty in nature:

[It] may not be a logical deduction, but to my imagination it is far more satisfactory to look at such instincts as the young cuckoo ejecting its foster-brothers,—ants making slaves,—the larvae of ichneumonide feeding within the live bodies of caterpillars,—not as specially endowed or created instincts, but as small consequences of one general law, leading to the advancement of all organic beings, namely, multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die.

As Dilley aptly puts it, “the argument relies on the theological assumption that it is improbable that an omnibenevolent, omnipotent and omniscient God would have intentionally designed creatures to cause or experience great suffering.” Indeed, the Origin “tacitly endorsed a particular view of God’s nature and moral obligations, and used this view as direct epistemic support for evolution and against” special creation.

According to Dilley, Darwin’s homology also “hinged upon theology.” In these arguments Darwin drew directly from Richard Owen’s On Limbs (1849), which also used theological claims to reject “divine purposive adaptations” as explanations for homologous structures. To Owen, “a respectable God would not produce a skeletal structure—whether in the whale’s fin or the chick’s head—more intricate than needed to accomplish the structure’s function.” Any plausible view of “divine creativity must accord with human notions of parsimony.” By invoking Owen’s On Limbs, Darwin implicitly relied upon the same line of reasoning to make his homology argument succeed.

Darwin accentuated the reliability of the empirical evidence by linking it to God’s moral character. It was God’s “divine integrity…that favoured the evolutionary account over the special-creation account.” Interestingly enough, according to Dilley, much of the empirical evidence for evolution in Darwin’s day was at a standstill. So “Darwin turned to the heavens, citing God’s moral probity as the adjudicating factor. Rightly or wrongly, Darwin used God’s (alleged) non-deceptive character as more than just a mooring for a general philosophy of nature; it functioned as direct epistemic support for descent with modification.”

And in arguing against William Paley’s Natural Theology (1802), specifically his design argument about the vertebrate eye, Darwin ushered in “unmistakable theological ideas about human epistemology.” “Human beings…cannot know that their own causal powers are relevantly similar to the Creator’s causal powers.” That is to say, certain features of God’s nature, such as his creative power, were “inaccessible to human beings.” In the Origin,” writes Dilley, “Darwin apparently drew upon this ‘more sublime theology’ to hold meekly that God’s creative powers were opaque to humans. Once again, he commissioned theological claims to strengthen his naturalized account of organic history.”

Dilley concludes that “contrary to conventional wisdom, the Origin did not so much separate science from theology as it articulated science from the vantage of semi-deism. Moreover, it proposed evolution by natural selection as an alternative to another theology-laden explanation, special creation. In the final analysis, the contrast in the Origin is not between theistic creationism and naturalistic evolution, but between theistic special creation and semi-deistic evolution—the latter with specific (and perhaps conflicted) notions of the existence, character, and actions and obligations of God.”

In Campbell’s essay, Darwin is generally characterized as an rhetorician, and, more specifically, the Origin as a rhetorical work from the ground up. For one, its brevity demonstrated a particular rhetorical aim. As Campbell argues, “that The Origin made its appearance as a single compact volume, accessible to a general audience,” rather than Darwin’s intended, massive, multi-volume work Natural Selection, a book on transmutation which he had been planning since 1837, is just one indication of its rhetorical strategy.

Completed only in nine-month’s time, the Origin also displays a particular ethos. As Darwin’s son Francis observed, “The reader [of the Origin] feels like a friend who is being talked to by a courteous gentlemen, not like a pupil being lectured by a professor.” This is in addition to its use of “everyday language,” found in the themes of “origins,” “selection,” “preservation,” “race,” “struggle,” and “life.” The Origin is at once charming, intimate, and almost colloquial.

Another rhetorical strategy used by Darwin in Origins, as we have already noted, is its deference to English natural theology. Indeed, “Darwin urges his views as more in keeping with proper respect to the ways of Providence than the views of his opponents.”

More importantly, Campbell persuasively argues that Darwin’s private letters and notebooks testify that Darwin “thought long and hard, not only about nature, but about persuasion, and that he went to great lengths, including not developing his views on the evolution of man, to minimize the shock of novelty The Origin would occasion.”

Hesketh, Dilley, Campbell, and many others have demonstrated that rather than separating theology from science, Darwin, implicitly and explicitly, invoked a positiva theology into the text of the Origin. This was indeed a powerful rhetorical strategy—but it was also a theological argument itself, about God’s character and the nature of His creation.

With Translation comes Interpretation: Translations of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

Posted on December 28, 2013 Leave a Comment

Robert Chambers believed that nature’s laws could explain the material universe. His Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (published anonymously) described a theory of everything, from the origin of the universe to the origin of life of humanity.

Earlier this month I mentioned reading through a collection of essays in the 2000 issue of The British Journal for the History of Science, with an Introduction by Jonathan R. Topham. The final essay in that collection comes from Nicholaas Rupke, “Translation Studies in the History of Science: the example of Vestiges.”

There Rupke argues that the three translations of Robert Chambers’ Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation—first into German in 1846, then into Dutch in 1849, and finally another German translation in 1851—invested the text with new meaning. Renditions of scientific texts into other languages can serve as “autochthonous cultural products.” “In the process of transfer and assimilation into a different culture,” Rupke explains, “texts can acquire an altered meaning. Translators relocate books, taking these away from the intellectual control of authors, repossessing the texts, possibly in the service of very different purposes than those for which the works were originally intended. Such alterations of meaning can be effected by new, additional prefaces, by footnote commentary, by other additions such as illustrations, by omissions and, most fundamentally, by the very act of cultural relocation.” In this way, translation studies demonstrate the “situatedness of scientific knowledge.”

The Vestiges was a publishing triumph. Four editions of the book appeared in just half a year, and eleven more during the period 1844-60. It also garnered in the English-speaking world a very substantial, critical response: “over eighty reviews which appeared in daily newspapers, popular weeklies and heavyweight quarterlies.” By contrast, there were almost no review of its English editions on the Continent. Prominent continental reviewing magazines Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen, Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, Heidelbergische Jahrbucher der Literatur, and Revue des deux mondes offered no reviews of the Vestiges. The book was also never translated into French, Italian, Spanish, Russian, or Swedish.

But translations did appear. According to Rupke, the first translation was into German in 1846, which was an adaptation of the third English edition of the Vestiges, by Adolf Friedrich Seubert (1819-1890), entitled Spuren der Gottheit in der Entwickelungs- und Bildungsgeschichte der Schöpfung: Nach William Whewell’s Indications of the Creator und der dritten Auflage der Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, für deutsche Leser bearbeitet. This translation does not provide its reader with either a preface or footnotes to the text; but it does include William Whewell’s (1794-1866) famous rebuttal of Vestiges in his Indications of the Creator (1845). Interestingly enough, Seubert “interwove the two texts, producing an almost seamless, integrated product by alternating chapters from the one with sections from the other.” In the English-speaking world, the two books were antithetical. Here, in Seubert’s translation, the concern “lay in something other than its transmutationism”; rather, it was put forward as evincing divine design in nature.

The Dutch translation of the Vestiges was carried out by Jan Hubert van den Broek (1815-1896) and appeared in 1849. It was an adaptation of the sixth English edition, under the title Sporen van de natuurlijke geschiedenis der schepping, of schepping en voortgaande ontwikkeling van planten en dieren, onder den invloed en het beheer der natuurwetten. This was a popular text, and underwent three more editions by 1854. Unlike the original English Vestiges, Broek included illustrations of principle plants and animals. And like Seubert’s German translation, Broek’s Dutch version added the opposing voice of Thomas Monck Mason’s (1803-1889) Creation by the Immediate Agency of God, as Opposed to Creation by Natural Law; being a Refutation of the Work Entitled Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1845). This Dutch translation was used, argues Rupke, as proof of divine order in nature and, more specifically, as aiding the stabilization of society under God and king in a process of recovery from the 1848 Revolution. The preface of the Sporen was written by Gerrit Jan Mulder (1802-1880), a man “disenchanted with the liberalization of post-1848 politics in the Netherlands and actively campaigned to keep a strong monarchy over and against parliamentary democracy.” To Mulder, the Vestiges was a salutary book, put forward in the “context of a form of Calvinist theism and of reactionary, monarchist politics.”

The second German translations comes from the “notorious materialist and anti-monarchist rebel,” Karl Vogt (1817-1895). Appearing in 1851, entitled Natürliche Geschichte der Schopfung des Weltalls, der Erde und der auf ihr befindlichen Organismen, begrundet auf die durch die Wissenschaft errungenen Tatsachen, Vogt’s translation included illustrations from 164 woodcuts, eighty-three footnotes, corrections, new information, and expressions of disagreement. As a leading champion of revolution and materialism, Vogt “highlighted Chambers’s deistic view that the laws of nature are regulations that in the beginning were enacted by divine will but since have operated autonomously.” Vogt argues in his brief introduction to Vestiges:

I recommend this book in a spirit of pure goodwill to the constitutional party in Germany, whose effectiveness before long will be limited to the innocent reading of innocent books. It will find in the book a constitutional Englishman, who has constructed a constitutional God, who, admittedly, in the beginning autocratically decreed laws, but then, out of his own volition, gave up his autocratic rule, letting the laws act in his place, by themselves, without himself exerting direct influence on his subjects. A beautiful example for sovereigns!

This God-talk is mere facetiousness, for Vogt did not believe in Chambers’ God, nor in any other God. Indeed, Vogt is famous for expressing the materialistic view that the human soul is nothing more than a function of the brain and that thought is a product of the brain in the same way that bile is secreted by the liver or urine is produced by the kidneys. And in a stunning footnote, Vogt declares that “the belief in an immortal soul being the only foundation for religion and church, its increasing untenability would soon lead to the collapse of ‘the whole nonsensical building.'” Thus Vogt’s German translation “interpreted the book as furthering the very revolutionary, anti-ecclesiastical and anti-monarchist ideals that” the Dutch and first German translations sought to counter.

Victorian Periodicals and Victorian Readership

Posted on December 28, 2013 Leave a Comment

A couple of other things I read over the holidays were J. Don Vann and Rosemary T. VanArsdel’s (eds.) Victorian Periodicals and Victorian Society (1994), and Alvar Ellegård’s short essay “The Readership of the Periodical Press in Mid-Victorian Britain” (1957).

Don Vann and VanArsdel have calibrated before, and Victorian Periodicals happens to be the third volume of an annotated bibliography project began in their MLA volume Victorian Periodicals: a Guide to Research in 1978. The contents of this third volume pertains to the professions, the arts, occupation and commerce, popular culture, and worker and student journals. There is a total of 18 essays on different types of periodicals: Law (Richard A Cosgrove), Medicine (M. Jeanne Peterson), Architecture (Ruth Richardson and Robert Thorne), Military (Albert Tucker), and Science (William H. Brock); Music (Leanne Langley), Illustration (Patricia Anderson), Authorship and the Book Trade (Robert A. Colby), and Theatre (Jane W. Stedman); Transport (John E.C. Palmer and Harold W. Paar), Financial and Trade Press (David J. Moss and Chris Hosgood), Advertising (Terrence Nevett), and Agriculture (Bernard A. Cook); Temperance (Olwen C. Niessen), Comic Periodicals (J. Don Vann), and Sport (Tony Mason); and finally Worker’s Journals (Jonathan Rose) and Student Journals (Rosemary T. VanArsdel and John S. North).

As with any collection of essays, this volume suffers from omissions and unevenness. But as a launching point for considering deeper studies into Victorian periodicals, it is most useful. It is a landmark study identifying “the ways that periodicals informed, instructed, and amused virtually all of the people in the many segments of Victorian life.”

The essays demonstrate the “pervasiveness of periodical literature in nineteenth-century British society.” Indeed, according to John S. North, the “circulation of periodicals and newspapers was larger and more influential in the nineteenth century than printed books, and served a more varied constituency in all walks of life.” The ubiquitous nature of Victorian periodical literature serves as a “vast repository of contemporary culture.”

What follows are some of the more interesting essays in this volume. William H. Brock’s “Science,” observes that “by the 1830s almost all initial scientific communication took place through specialist periodicals rather than books.” According to one nineteenth-century author, “periodical publications are a surer index of the state of progress of the mind, than the works of a higher character.” Nineteenth-century science journals and periodicals can thus provide the “collective view of science” of Victorian society.

Another instructive essay comes from J. Don Vann on “Comic Periodicals.” The Victorian comic periodical typically contained jokes, comic verse, riddles, parodies, caricatures, puns, cartoons, and satire. Some of the earliest were Satirist (1808-14) and Age (1825-43), well-known for their vicious and scurrilous attacks on people, which resulted in frequent lawsuits, but increased circulation and advertising revenues. But of all comic periodicals of the nineteenth century, “more has been written about the history of Punch (1841-1900[1992]) than about all the other Victorian comic periodicals combined.” Its appeal lies in the fact that from the outset it was a magazine designed to do more than amuse its readers; it was designed to “ridicule political parties when they became nothing more than ‘sycophancy of a degraded constituency,’ to ensure that prisons were for correction of offenders rather than places of punishment for those who were simply poor and unlucky, and to attack capital punishment.” In addition to appealing to “all lovers of wit and satire,” Punch “appealed to ‘gentlemen of education’ and thus found a place in the library and drawing room.” Or as another author eloquently put it:

The press is the corrector of abuses; the regressor of grievances; the modern chivalry that defends the poor and helpless and restrains the oppressor’s hand in cases where the law is either too weak or too lax to be operative, or where those who suffer have no means of appealing to the tribunals of their country for protection. It is, to, the scourge of vice; where no law could be effective, where the statue of law does not extend, where the common law fails—the law of the press strikes the offender with a salutary terror, causes him to shrink from the exposure that awaits him, and not infrequently arrests him in the career of oppression or of guilt.

Finally, in an essay on “Student Journals” by Rosemary T. VanArsdel and John S. North, we see how the university “provided an ideal atmosphere during the nineteenth century to encourage student journalism.” A community of many constituencies, university journals offered material from faculty, administrators, chancellors and boards of trustees, and students with their societies and organizations. From satire, parody, essays, and lampoons, to expository prose in editorial or news stories, descriptive prose in features, or literary expression in verse, drama, or narrative prose, student magazines and university journals provide an excellent source of educated Victorian high society. VanArsdel and North include selections (1824-1900) from England’s Cambridge University, Durham University, London University, University of Manchester, and Oxford University; from Ireland’s University of Dublin, Trinity College, Dublin, and University College, Dublin; from Scotland’s Aberdeen University, University of Edinburgh, Glasgow University, and St Andrews; and from Wales’ University College of Wales.

Alvar Ellegård’s astonishing Darwin and the General Reader (1958, 1990), which investigated over one hundred newspapers and periodicals to extract how contemporaries received Darwin’s theory, is well-known among historians of science. But prior to that 1958 publication, Ellegård published “The Readership of the Periodical Press in Mid-Victorian Britain” (1957), a paper estimating “the size and various other characteristics of the publics of the Mid-Victorian periodicals.” According to Ellegård, the press is where the age portrays itself. In the 1860s, for example, because the “pace of life was quickening,” the public “demanded more frequent and more easily digestible information about happenings in the world of letters and ideas.” Thus in the mid-Victorian period there was an explosion of weekly, monthly and quarterly periodicals. In his Directory, Ellegård includes the “more important periodicals that were in some degree organs of opinion,” giving a “fairly reliable picture of the sort of periodicals that were most important in expressing, and most influential in forming, public opinion on the wider questions of the day.”

This Directory is helpfully divided into five main groups: newspapers, weekly reviews, fortnightly and quarterly reviews, monthly magazines, and weekly journals and magazines. Listed with each periodical are dates of establishment, price and estimated circulation, and brief descriptions and likely readership. There follows a treasure trove of primary source information. In newspapers proper, Ellegård lists the Daily News, Daily Telegraph, Manchester Guardian, Morning Advertiser, Morning Post, Standard, Star, and Times; evening newspapers included are Echo, Globe, and Pall Mall Gazette; weekly newspapers included are John Bull, Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper, News of the World, Observer, Reynold’s Weekly Newspaper, Saint James’ Chronicle, Sunday Times, Weekly Dispatch, and Weekly Times; specifically religious newspapers included are British Standard, Methodist Recorder, Record, Watchman, and Universe.

The next group includes weekly reviews. Here we find the literary reviews of Athenaeum, British Medical Journal, Critic, Economist, Examiner, Lancet, Leader, Literary Gazette, London Review, Nature, Parthenon, Press, Public Opinion, Reader, Saturday Review, and Spectator. Religious weekly reviews included are Church Review, English Churchman, English Independent, Freeman, Guardian, Inquirer, Nonconformist, Patriot, Tablet, and Weekly Review.

Fortnightly and quarterly reviews included are Academy, Contemporary Review, Edinburgh Review, Fortnightly Review, North British Review, Quarterly Review, and Westminster Review. Some of the better known scientific reviews included are Annals and Magazine of Natural History, Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, Geological Magazine, Intellectual Observer, Natural History Review, Popular Science Review, Quarterly Journal of Science, Recreative Science, Student, and Zoologist. On the religious front Ellegård includes British and Foreign Evangelical Review, British Quarterly Review, Christian Observer, Christian Remembrancer, Dublin Review, Ecclesiastic, Eclectic Review, Friend, Friends’ Quarterly, Home and Foreign Review, Journal of Sacred Literature, Literary Churchman, London Quarterly Review, Month, National Review, Rambler, and Theological Review.

Monthly magazines included are Argosy, Belgravia, Bentley’s Miscellany, Blackwood’s Magazine, Broadway, Cassell’s Magazine, Cornhill, Dublin University Magazine, Fraser’s Magazine, Gentleman’s Magazine, London Society, Macmillan’s Magazine, New Monthly Magazine, St James’ Magazine, St Paul’s Magazine, Temple Bar, Tinsley’s Magazine, and Victoria Magazine.

Weekly journals and magazines sold in weekly parts included are All the Year Around, Cassell’s Illustrated Family Paper, Chamber’s Journal, Family Herald, Fun, Good Words, Illustrated London News, Leisure Hour, London Journal, London Reader, Once a Week, Punch, Tomahawk, and Vanity Fair.

Like J. Don Vann and Rosemary T. VanArsdel’s Victorian Periodicals and Victorian Society Alvar Ellegård’s short essay “The Readership of the Periodical Press in Mid-Victorian Britain” provides little commentary on nineteenth-century periodicals itself. Rather, their strength lies in their ability to act as reference points, leading the reader to pursue further research from one of the many primary sources listed in these two helpful books.

Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False

Posted on December 27, 2013 2 Comments

Thomas Nagel’s Mind & Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False (2012) has caused quite a stir. Maria Popova at Brain Pickings finds “Nagel’s case for weaving a historical perspective into the understanding of mind particularly compelling.” She sees it as “a necessary thorn in the side of today’s all-too-prevalent scientific reductionism and a poignant affirmation of Isaac Asimov’s famous contention that ‘the most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious.'”

While Louis B. Jones argues in the ThreePenny Review that Nagel’s “project seems like a glance in the right direction,” P.N. Furbank, in the same review article, argues that he is “fatally unspecific,” “impalpable,” and “reckless.”

Edward Fesser at First Things declares that Nagel’s work “marks an important contribution to the small but significant Aristotelian revival currently underway in academic philosophy of science and metaphysics.”

Brian Leiter and Michael Weisberg over at The Nation find Nagel’s argument perplexing, quixotic, unconvincing, and highly misleading; his book is declared “an instrument of mischief.”

John Dupré at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews also found the book “frustrating and unconvincing.”

Alva Noë, in a series of articles for NPR, “Are the Mind and Life Natural?,” “Moving Beyond Political Correctness,” and “Arguing the Nature of Values,” rejects some of Nagel’s convictions, but also finds Leiter and Weisberg’s review “superficial and unsatisfying.” It is, in the end, a “worthwhile” book.

Philosopher Simon Blackburn’s review in New Statesmen find’s Nagel’s confession to “finding things bewildering” quite charming. But ultimately regrets its appearance. “It will only bring comfort to creationists and fans of ‘intelligent design,'” he says, and “if there were a philosophical Vatican, the book would be a good candidate for going on to the Index.”

Alvin Plantinga, whose own Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion, and Naturalism (2011) sits beside Nagel’s book on my bookshelf, argues in the New Republic that Nagel makes a strong and persuasive case against materialist naturalism. According to Plantinga, “if Nagel followed his own methodological prescriptions and requirements for sound philosophy, if he followed his own arguments wherever they lead, if he ignored his emotional antipathy to belief in God, then (or so I think) he would wind up a theist.”

More recently, John Horgan at The Globe and Mail, states he shares “Nagel’s view of science’s inadequacies,” but was disappointed by his dry, abstract style. Like Popova, Horgan recommends Nagel’s book “as a much-needed counterweight to the smug, know-it-all stance of many modern scientists.”

Adam Frank at NPR sees “Nagel’s arguments against Darwin…[as] a kind wishful thinking.” Nevertheless, he finds his “perspective bracing.” “[O]nce I got past Nagel’s missteps on Darwin,” Frank writes, “I found his arguments to be quite brave, even if I am not ready to follow him to the ends of his ontology. There is a stiff, cold wind in his perspective. Those who dismiss him out of hand are holding fast to a knowledge that does not exist. The truth of the matter is we are just at the beginning of our understanding of consciousness and of the Mind.”

In the New York Review of Books, H. Allen Orr sees Nagel’s work as “provocative,” reflecting the “efforts of a fiercely independent mind.” In important places, however, Orr believes that it is “wrong.”

Richard Brody at The New Yorker is “immensely sympathetic to Nagel’s line of thought.”

Finally, at The New York Times, Thomas Nagel responds to both his critics and supporters with a brief restatement of his position. He argues that “the physical sciences can describe organisms like ourselves as parts of the objective spatio-temporal order – our structure and behavior in space and time – but they cannot describe the subjective experiences of such organisms or how the world appears to their different particular points of view.” Purely physical descriptions of neurophysiological processes of experience will always leave out the subjective essence of experience. The physical sciences, therefore, leave an important aspect of nature unexplained.

The sciences, if it wishes to have the full domain of explanation, “must expand to include theories capable of explaining the appearance in the universe of mental phenomena and the subjective points of view in which they occur.”

Nagel sees two responses to this claim as self-evidently false: namely, (a) that the mental can be identified with some aspect of the physical; and (b) by denying that the mental is part of reality at all. He also sees a third response as completely implausible, (c) that we can regard it as a mere fluke or accident, an unexplained extra property of certain physical organisms. But by rejecting all three responses he does not see how it entails (d) that we can believe that it has an explanation, but one that belongs not to science but to theology—in other words that mind has been added to the physical world in the course of evolution by divine intervention.

According to Nagel, “a scientific understanding of nature need not be limited to a physical theory of the objective spatio-temporal order.” In other words, Nagel wants an “expanded form of understanding.” “Mind,” he continues, “is not an inexplicable accident or a divine and anomalous gift but a basic aspect of nature that we will not understand until we transcend the built-in limits of contemporary scientific orthodoxy.” Although Nagel does not “believe” the theistic outlook, he does admit that “some theists might find this acceptable; since they could maintain that God is ultimately responsible for such an expanded natural order, as they believe he is for the laws of physics.”

The God of Science on the Neck of her Enemies

Posted on December 26, 2013 1 Comment

Theology and Parsondom are in my mind the natural and irreconcilable enemies of Science. Few see it but I believe that we are on the Eve of a new Reformation and if I have a wish to live 30 yrs, it is to see the God of Science on the necks of her enemies.

Theology and Parsondom are in my mind the natural and irreconcilable enemies of Science. Few see it but I believe that we are on the Eve of a new Reformation and if I have a wish to live 30 yrs, it is to see the God of Science on the necks of her enemies.

Thomas Henry Huxley to Frederick Dyster (30, January 1859).

Over the holidays, I had the chance to read a couple of different things. The first was Ian Hesketh’s Of Apes and Ancestors: Evolution, Christianity, and the Oxford Debate (2009). At 128 pages, including notes, it is a quick read. Although short, Of Apes and Ancestors aptly synthesizes a remarkable amount of scholarship on the famous (or infamous) Huxley-Wilberforce debate at Oxford in 1860. Its aim is to examine, from the perspective of each key participant, including Charles Darwin, Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, T.H. Huxley, Richard Owen, and Joseph Hooker, the Oxford debate; and, moreover, the way it has been “mythologized” then and now.

Hesketh begins with Darwin as a “historian of natural history.” Darwin was neither confrontational nor combative. He preferred to express himself in written word, but even then he limited himself to personal letters and revisions to his Origin of Species (1859). Hesketh points out that Darwin “answered his critics not by writing responses to the many periodicals and newspapers where reviews of the Origin appeared or by debating his foes in the public sphere of scientific and learned societies…he responded by continually revising the Origin in order to take into account new evidence but also new problems exposed by critics and friends alike.” Perhaps one reason for this was Darwin’s invariable illness, particularly his “constant stomach churning, flatulence, and retching.”

Hesketh also points out that despite illness, Darwin was a meticulous and patient observer of nature. Darwin published his Journal of Researches in 1839 (renamed later The Voyages of the Beagle) based on his famous HMS Beagle voyage (1831-1836), becoming instantly “something of a celebrity among naturalist circles.” When it came time to publishing his Origin, Darwin was careful not to “smash received wisdom or to overturn the central tenets of Christian thought.” Indeed, as Hesketh writes, “the Origin, far from being the secular text it is often presented as, established a theory of evolution from within a Christian framework.” In its first edition, and even more so in its second, the Origin presented the “evolving world” as guided by a “divine being.”

Despite his conciliatory efforts, Darwin’s Origin invited many critics—but more from the scientific community than the established church! For example, Richard Owen (1804-1892), comparative anatomist and Hunterian Professor at the Royal College of Surgeons, wrote a strident review of Origin in the April 1860 issue of the Edinburgh Review. “Owen dismissed the idea that natural selection could do what Darwin claimed and suggested alternative possibilities, such as his own theory of archetypes.”

Darwin was also privately chastened by Baden Powell (1827-1860), Savillian Professor of Mathematics at Oxford. On Powell’s account, Darwin had failed to acknowledge his predecessors. Both Charles Lyell (1797-1875) and Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), for example, had acknowledged their debts to predecessors and, according to Powell, Darwin ought to as well.

One of Darwin’s most fiercest critics was the geologist Adam Sedgwick (1785-1873). Incidentally, Darwin was once a student of Sedgwick. He admitted that he admired parts of Darwin’s Origin, but added that “other parts made him laugh ’till my sides were almost sore’ and that he had read much of the book with ‘profound sorrow.'” Darwin, according to Sedgwick, had “deserted” the “true method of induction.”

In January of 1860, Darwin finally decided to write “An Historical Sketch” of the idea of transmutation, which would act as a preface to the American and German editions of the Origin. He begins with French naturalists Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772-1844), then moves on to lesser known figures such as a Dr. W.C. Wells, Reverned W. Herbert, Patrick Matthew, and Scottish zoologist Robert Edmund Grant (1793-1874). Darwin then offers pointed criticism against the anonymous author (Robert Chambers [1802-1871]) of the popular Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844). Yet he also wrote that the Vestiges provided an “excellent service in this country in calling attention to the subject [of evolution], in removing prejudice, and in thus preparing the ground for the reception of analogous views.” Darwin goes on to describe the evolutionary views of Henry Freke, Herbert Spencer, Charles Naudin, Alexandre Keyserling, Henry Schaaffhausen, Henri Locoq, Baden Powell, Alfred Wallace, and Karl Ernst von Baer, concluding with T.H. Huxley and Joseph Hooker. Thus rather than defending his theory through periodical press or public debate, Darwin offered a subtle rebuttal to his critics in his historical sketch, which he penned about a month before the Oxford debate.

Hesketh follows in the next chapter with a fascinating portrait of Samuel Wilberforce (1805-1873). Samuel’s father, William Wilberforce (1759-1833) was, of course, the Great Emancipator, fighting “against the slave trade as leader of the evangelical Clapham Sect.” When Samuel was twelve, his father began writing letters of purpose and guidance to him. “There are more than six hundred of these letters,” writes Hesketh, “and they served as the foundation of his moralistic belief system.” He wrote to him to “watch unto prayer,” to “maintain such a state of mind” that will “render you fit at any time,” “to compose your spirits and engage in that blessed exercise,” to “walk by faith and not by sight,” and to “do all in the name of our Lord Jesus.” When Samuel went off to study at Oxford his father wrote that now was the time for him to become his “own master,” and to prepare himself for he “will be tried to a different standard from that which is commonly referred to, and be judged by a more rigorous rule; for it would be folly, rather than merely false delicacy, to deny that from various causes my character is more generally known than that if most men in my rank in life.”

While at Oxford Samuel encountered the Tractarians. The Tractarians believed that the “revival of evangelicalism…had necessarily weakened the spiritual and corporate roles of the established Church.” This internal conflict within Christianity between the High (Tractarian) and Low (evangelical) Church in the 1830s struck a presentiment fear in Samuel. He saw these fears fulfilled in the 1850s and 1860s when the liberal Board Church Movement attempted to “modernize the Church,” and “reshape Christianity to conform to science.” As Hesketh notes, “in 1860, three months before Wilberforce denounced evolution at the Oxford debate, the Broad Church Movement published its Essays and Reviews,” which argued that Christianity’s relevance depended entirely on its “reasonableness.” Written by seven different authors, six of whom were well-known Anglican clergymen, Essays and Reviews “challenged orthodox Christianity to face up to scientific and historical evidences and to abandon the lies and half-truths that had been perpetuated over the centuries.” What is more, when Samuel’s wife died in 1841, he entered a “crisis of faith that [he] overcame through a renewed devotion to the Church of England.” Her death was a sign for him to devote himself entirely to the church. “Defending Christian truth would become Samuel’s purpose in life, ‘his burden of desolate service.'” This deeply devoted Anglican bishop would conclude that the Essays and Reviews—or anything else that was contrary to orthodox Christianity—was pure heresy.

Hesketh is careful to note that Wilberforce did not view science as “evil,” however. Indeed, Wilberforce “enjoyed thinking about scientific questions and debates of the day.” He was even a great supporter of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS). Thus when Darwin’s Origin appeared, he offered scientific arguments against it; namely, that breeding negated natural selection, and the fact that there was only meager evidence for transitional forms. In other words, for Wilberforce Darwin’s theory was scientifically wrong.