God and Life in the Universe

Posted on June 5, 2024 Leave a Comment

Here I will discuss Andrew Davison’s Astrobiology and Christian Doctrine: Exploring the Implications of Life in the Universe (2023).

Davison wants to prepare Christians for the potential discovery of extraterrestrial life by using the latest advances in astrobiology. Davison argues that anticipating the discovery of life elsewhere in the universe can help theology remain dynamic and relevant. He suggests that such preparation can mitigate any crisis of faith that might arise from such a discovery and asserts that considering extraterrestrial life can offer new insights into longstanding theological questions. Quoting Anglo-Catholic theologian Eric Mascall, Davison writes: “Theological principles tend to become torpid for lack of exercise, and there is much to be said for giving them now and then a scamper in a field where the paths are few and the boundaries undefined.”

Davison’s approach is thus proactive, recognizing the significant impact that scientific discoveries can have on religious belief systems. He emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary dialogue, which is crucial for contemporary theology. In some ways, Davison’s approach reminds me of Karl Rahner’s concept of the “anonymous Christian,” which prepared the Christian theological framework to engage with non-Christian religions, showing how theology can be adaptable to new realities.

Some, however, might contend that Davison’s forward-thinking approach might assume a level of adaptability that simply cannot exist, which would potentially undermine both scientific findings and established religious doctrines. I will return to this problem later in this review.

Part I of the book focuses on Creation. In his first chapter Davison examines the historical and theological tradition of “multiple worlds.” Indeed, he traces the idea back to ancient and medieval Christian thinkers who speculated about the existence of other worlds, illustrating nicely how the concept is not new to Christian theology.

He explores how these speculations have been reconciled with the doctrine of creation, emphasizing that the notion of multiple worlds does not necessarily diminish the significance of Earth or humanity’s place in creation. Thomas Aquinas, for example, considered the possibility of many words, but did not see it as diminishing human value or the uniqueness of creation. More recently, C. S. Lewis, in his popular Space Trilogy, explores similar themes of multiple inhabited worlds and the theological implications of such a cosmos.

Davison next explores the theological parallels between angels and the potential existence of extraterrestrial beings. Again, he looks at how religious writers have historically viewed angels and how these views might intersect with contemporary ideas about extraterrestrial life. He suggests that angels could be seen as a form of extraterrestrial life, thereby broadening our understanding of both concepts. For example, in Dante’s Divine Comedy, which uses a hierarchy of angels to explore broader theological themes, one could borrow this theological thinking to enrich our understanding of the greater cosmic order. However, the comparison between angels and extraterrestrial life is speculative and risks conflating distinct theological and scientific categories, potentially leading to theological confusion.

Chapter 3 continues to explore the theological significance of discovering extraterrestrial life. Davison discusses how such a discovery might affect doctrines of creation and salvation, considering whether extraterrestrial beings would fall under the same theological categories as humans. He reflects on the potential need to rethink doctrines like original sin and the universality of salvation. One can clearly see parallels to Teilhard de Chardin’s The Phenomenon of Man in this chapter, with his attempt to reconcile evolutionary science with Christian theology. But of course, the mention and comparison of de Chardin brings the question (and concerns) with how these speculations align with orthodox Christian doctrine.

Davison then addresses the theological implications of the vastness of space and the apparent emptiness between stars and galaxies. “He considers how this vastness relates to God’s omnipresence and the fullness of creation, discussing theological interpretations of space’s expansiveness and what it reveals about the nature of God and creation. “The vastness of space,” he writes, “can be seen as a testament to the glory and plenitude of God’s creation.” John Polkinghorne’s writings, which explore the interface of science and religion, provide a useful comparison in their efforts to reconcile scientific understanding with theological concepts. But as is the case with both authors, the treatment of the vastness of space is overly poetic, lacking in practical theological insight. This reader feels that Davison does not sufficiently address the existential implications of humanity’s relative insignificance in the cosmos.

Part II looks more deeply at Revelation and Theological Knowledge. Davison begins by examining how the potential discovery of extraterrestrial life might impact the Christian understanding of divine revelation, and particularly the universality of the Gospels. However, he contends that the “concept of revelation must be flexible enough to accommodate new discoveries while remaining true to its core tenets.” Of course, the question here is: what are the core tenets of Christian faith! Again, we might reference to Rahner’s “anonymous Christian.” And this again brings in the nagging question of how both approaches might potentially undermine the uniqueness of Christian revelation, leading to a form of theological relativism.

Perhaps sensing the increasing dilemma of his approach, Davison next examines how the potential existence of extraterrestrial life might influence the understanding of the Trinity and the language used to describe God. He considers whether extraterrestrial beings might have different conceptions of the divine and how this could enrich human theological discourse. “Different conceptions of the divine among extraterrestrial beings could enrich our theological discourse.” But once again, the same concerns remain. Process theologians like Alfred North Whitehead, who view God’s nature as dynamic and relational, provide a parallel in their willingness to rethink traditional theological categories in light of new philosophical insights. But the speculative nature of this chapter may be seen as a departure from orthodox Trinitarian theology.

Continuing his reassessment of Christian theology, Davison explores the concept of Imago Dei, the belief that humans are created in the image of God, and how it might be reinterpreted in light of extraterrestrial life. “The concept of Imago Dei,” he contends, “may need to be broadened to include multiple species, each reflecting different aspects of the divine.” He then turns to the question of human uniqueness in the universe.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Wolfhart Pannenberg was known for his emphasis on the dynamic and relational aspects of the Imago Dei in the context of human community and relationships.

Atheists and Atheism before the Enlightenment

Posted on June 5, 2024 Leave a Comment

Michael Hunter, Emeritus Professor of History at Birkbeck, University of London, has published a new book: Atheists and Atheism Before the Enlightenment: The English and Scottish Experience (2023). Here I wish to give a brief overview of its contents. Over time I will return to this post to add more content and thoughts.

In his introduction, Hunter outlines the book’s focus on atheism in early modern England and Scotland, emphasizing the nature and perception of atheism during the period. He begins by defining atheism not just as a disbelief in God but as a broader cultural and intellectual phenomenon. The chapter, moreover, discusses the complex interplay between genuine irreligion and the exaggerated fear of atheism, which was often fueled by religious and political agendas. Hunter highlights the “assurance” that characterized atheists, portraying them as confident and articulate in their disbelief, contrasting with the prevalent religious doubt among the general populace.

Chapter two examines in more detail the terminology and conceptual challenges in studying atheism in early modern England. Hunter places “atheism” in quotation marks to indicate the fluidity of its meaning at the time, which ranged from outright denial of God’s existence to broader accusations of heresy and moral deviance. The chapter also explores the societal and intellectual anxieties surrounding irreligion, noting how the fear of atheism often overshadowed the actual presence of atheists. Hunter analyzes key texts and figures from the period, revealing how the discourse on atheism was shaped by rhetorical exaggeration and moral panic.

Chapter 3 looks at the intersection of atheism and religious doubt among devout believers. Hunter references Alec Ryrie’s work on the emotional history of doubt, contrasting the overt irreligion of atheists with the private, often unspoken doubts of the faithful. This chapter argues that understanding the covert doubts of religious individuals is crucial for a comprehensive picture of early modern atheism. Hunter discusses notable figures and texts that reveal the inner struggles of believers, highlighting how these doubts contributed to broader religious and philosophical debates.

Chapter 4 investigates the state of atheism and irreligion in the period following 1660, particularly during the Restoration. It highlights the persistence of many characteristics from the pre-Civil War era, such as the broad and inclusive definitions of atheism, the conflation of real and imagined irreligious attitudes, and the sensationalized stereotypes created by anti-atheist literature. This literature combined elements of naturalism, secularism, and irreverent wit, often associated with coffee-house culture, to create a composite “atheist” stereotype. Indeed, the chapter emphasizes the role of this stereotype in promoting concern among the devout about immorality and the potential for deviation from orthodox beliefs.

For instance, Hunter explores notable figures and episodes from this period, including the subversive writings of Sir Walter Ralegh and the scandalous accusations against the poet Christopher Marlowe. The chapter underscores the exaggerated nature of anti-atheist rhetoric, which sought to alarm the religious and promote greater zeal by equating minor deviations from orthodoxy with outright atheism.

Hunter argues that this exaggerated fear of atheism was instrumental in expressing broader anxieties about religious doubt and the potential for articulate irreligion. The chapter concludes with a discussion on the influence of Thomas Hobbes and the perceived spread of “Hobbism” in the years after 1660, setting the stage for further exploration in subsequent chapters.

Chapter 5 examines the relationship between atheism and the aristocracy in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Hunter discusses how certain aristocrats, influenced by intellectual currents and social circles, began to exhibit irreligious tendencies. He highlights figures like the physician William Cheselden and the antiquary Joseph Ames, who were suspected of atheism, and Martin Folkes, known for his infidel views. Hunter describes how these aristocrats’ views and behaviors, often articulated in private circles or informal settings like coffee-houses, contributed to a growing culture of skepticism and irreligion.

The chapter also addresses the influence of deism among the aristocracy, with prominent doctors like Sir Hans Sloane and Richard Mead advocating for natural explanations of phenomena traditionally attributed to divine intervention. Hunter suggests that these developments gradually opened the door to more widespread acceptance of non-theistic perspectives, despite the ongoing dominance of orthodox religious beliefs

Chapter 6 explores the spread of irreligious ideas among the broader public, focusing on how these ideas were disseminated through various channels. Hunter discusses the role of pamphlets, books, and public debates in making skeptical and atheistic ideas accessible to a wider audience. He examines the influence of popular literature and the role of public intellectuals in challenging orthodox religious views.

The chapter also highlights the ways in which irreligious ideas were often cloaked in humor or satire to avoid direct confrontation with authorities. Hunter also addresses the impact of educational institutions and the gradual shift in public attitudes towards more secular and critical perspectives on religion. The chapter suggests that while outright atheism remained rare, the seeds of skepticism were being sown more broadly across society.

Chapter 7 looks into the intellectual underpinnings of irreligion, examining the philosophical and scientific developments that challenged traditional religious beliefs. Hunter discusses the impact of the Enlightenment and the rise of empirical science on the credibility of religious explanations. The chapter explores the works of key philosophers and scientists who questioned the existence of God and promoted naturalistic explanations for phenomena.

Hunter also addresses the role of higher education and scholarly societies in fostering an environment where irreligious ideas could be debated and developed. He highlights the contributions of figures like John Locke and Isaac Newton, whose ideas, while not explicitly atheistic, paved the way for a more secular understanding of the world. The chapter concludes by discussing the gradual shift towards a more critical and questioning approach to religion among the educated elite.

Chapter 8 investigates the broader social implications of the rise of atheism and irreligion. Hunter explores how these ideas influenced social norms, political ideologies, and cultural practices. He examines the tension between religious authorities and proponents of atheism, highlighting key conflicts and debates that shaped public discourse.

The chapter also addresses the ways in which irreligious ideas affected moral and ethical considerations, including attitudes towards issues like marriage, education, and governance. Hunter suggests that while atheism was far from mainstream, its increasing visibility challenged traditional power structures and contributed to the gradual secularization of society. The chapter concludes by reflecting on the legacy of this period for modern secular thought and the ongoing debates about the role of religion in public life

The conclusion of Atheists and Atheism before the Enlightenment synthesizes the findings from the preceding chapters to draw overarching conclusions about the state of atheism and irreligion in pre-Enlightenment England and Scotland. First, atheistic ideas were predominantly expressed orally rather than in written form. This oral nature of atheistic expression made it challenging for authorities to regulate and suppress such ideas effectively. The contrast between individuals like Tinkler Ducket, who attempted to destroy incriminating letters, and more vocal atheists who openly expressed their views, highlights the varied responses to atheism during this period.

Second, Hunter draws attention to the differences between Scotland and England. In Scotland, a more homogenous public life allowed for harsher responses to atheism, such as Thomas Aikenhead’s execution. In contrast, England’s more diffuse public life meant that while outrage over atheism was common, it was harder to enforce punitive measures.

Third, figures like John Toland, who sought notoriety through public displays of heterodoxy, and George Turnbull, who initially embraced freethinking but later reverted to orthodoxy, exemplify the varied trajectories of individuals engaged with atheistic ideas. The presence of freethinking elements in Scottish culture, despite its ostensibly orthodox façade, suggests a more complex intellectual landscape than previously acknowledged.

Fourth, in England, the reaction to atheism included legislative measures like the Blasphemy Act of 1698, which targeted anti-Trinitarian opinions and other forms of irreligion. Public discourses, such as the Boyle Lectures, aimed to counter atheistic sentiments, reflecting widespread concern about the influence of irreligious ideas.

And with this, Hunter comes full circle to his earlier work on the Boyle Lectures.

God and Mammon

Posted on June 4, 2024 Leave a Comment

In this post I will be discussing William Cavanaugh’s Being Consumed (2008) and Eugene McCarraher’s The Enchantment of Mammon (2019).

By 1883, Émile Zola observed that, in Paris, church doctrine had been replaced by the religion of

the cash register (cited in New York Times Book Review)

The Stillborn God

Posted on May 11, 2024 3 Comments

After a long hiatus, I will be writing again this summer. The first book I want to review here is Mark Lilla’s The Stillborn God: Religion, Politics, and the Modern West (2008).

Religious Secularity

Posted on January 23, 2021 Leave a Comment

In his wide-ranging Economy and Society (1921), German sociologist Max Weber contended that rationalized technological power structures intended to control life would eventually collapse into “emotionalism” and irrationality:

The objectification of the power structure, with the complex of problems produced by its rationalized ethical provisos, has but one psychological equivalent: the vocational ethic taught by asceticism. An increased tendency toward Hight into the irrationalities of apolitical emotionalism in different degrees and forms, is one of the actual consequences of the rationalization of coercion, manifesting itself wherever the exercise of power has developed away from the personalistic orientation of heroes and wherever the entire society in question has developed in the direction of a national “state.” Such apolitical emotionalism may take the form of a flight into mysticism and an acosmistic ethic of absolute goodness or into the irrationalities of non-religious emotionalism, above all eroticism. Indeed, the power of the sphere of eroticism enters into particular tensions with religions of salvation. This is particularly true of the most powerful component of eroticism, namely sexual love. For sexual love, along with the “true” or economic interest, and the social drives toward power and prestige, is among the most fundamental and universal components of the actual course of interpersonal behavior.

Similarly prescient and equally wide-ranging, Oswald Spengler argued in his The Decline of the West (1918) that materialism would become unbearable and that people would therefore feel impelled to toy with esoteric cults and beliefs as a means of escape. He called it the “second religiousness”:

It appears in all Civilizations as soon as they have fully formed themselves as such and are beginning to pass, slowly and imperceptibly, into the non-historical state in which time-periods cease to mean anything […] The Second Religiousness is the necessary counterpart of Caesarism, which is the final political consitution of Late Civilizations; it becomes visible, therefore, in the Augustan Age of the Classical and about the time of Shi-hwang-ti’s time in China. In both phenomena the creative young strength of the Early Culture is lacking. Both have their greatness nevertheless. That of the Second Religiousness consists in a deep piety that fills the waking-consciousness—the piety that impressed Herodotus in the (Late) Egyptians and impresses West-Europeans in China, India, and Islam—and that of Caesarism consists in its unchained might of colossal facts.

These observations are yet another reason to reject the misleading interpretation that secularism means simply the replacement of a worldview that is religious with one that is not. Modern society is awash with religiosity. This view has, in part, been confirmed by Tara Isabella Burton’s recent book, Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World (2020). According to Burton, we do not live in a godless world. Rather, we live in a profoundly anti-institutional one, where we have rendered “ourselves simultaneously parishioner, high priest, and deity” (Burton 2020). The recent emergence of the “Nones” should actually be called the “Remixed,” who seek to satisfy the deep need for meaning, purpose, community, and ritual with new and personalized intuitional faiths rather than traditional institutional counterparts. The growing religiously unaffiliated offers adherents a new religion of emotive intuition, of aestheticized and commodified experience, of self-creation and self-improvement. This, again, is not the rejection of religion, but rather its remixing.

Secularization, in short, is not the eraser of religion. Rather, it is the flourishing of anti-Christian religions. This religious secularity has usually come in the form of humanism. Indeed, anthropologist Margaret Mead, in her autobiography, Blackberry Winter: My Earlier Years (1975), praised secular humanism, calling for its spread throughout the world.

Other works can be cited, but what should be clear is that what is regarded as a struggle between religious and secular is really, and has always been, a struggle between religions.

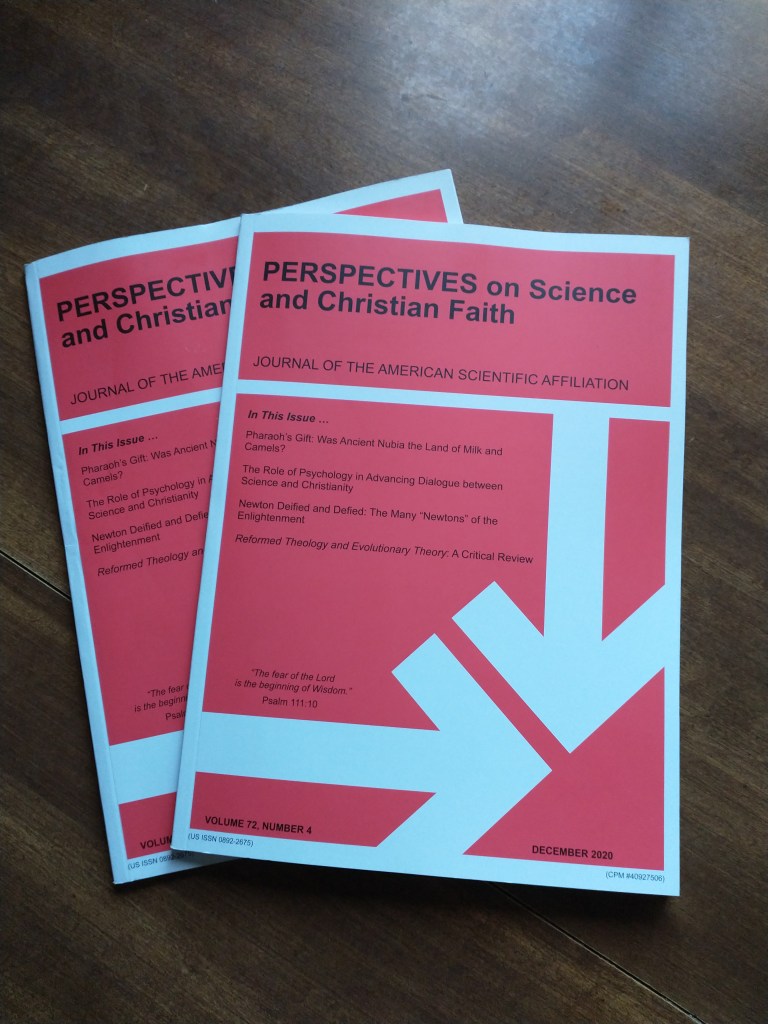

The Many “Newtons” of the Enlightenment

Posted on December 5, 2020 Leave a Comment

The American Scientific Affliation’s (ASA) latest issue of Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith has published my recent study on Isaac Newton and his unique theological perspective. You can either find the issue in your local university library or you can become a member of the ASA and subscribe here.

Science, Religion, and the Protestant Tradition: Talk at Covenant Presbyterian Church

Posted on November 21, 2020 Leave a Comment

I recently had the privilege to speak about the history of Christianity and science and my own interpretation of the origins of the “conflict thesis” with the folks at Covenant Presbyterian Church here in Madison, Wisconsin. I had a great time and very much appreciated the comments and questions after each lecture. Below you’ll find Parts 1 and 2.